“I suppose it was just to prove that they had power in their hands."

Virginity tests are an extremely invasive and inaccurate test carried out to find evidence of vaginal intercourse.

The traumatising test typically involves an internal examination of a woman’s genitalia, in order to check if the hymen is intact.

Unfortunately, virginity tests are still very much a common practice within the 21st century. In 2018, the World Health Organisation expressed:

“Virginity testing is a long-standing tradition that has been documented in at least 20 countries spanning all regions of the world.”

A 2015 article by The Week stated that the practice of virginity tests “occurs in deeply traditional or religious societies where virginity is highly prized.”

However, the humiliating practice of virginity tests also has a long history within the UK. Virginity tests were in fact conducted on Indian and Pakistani women by British Immigration officials in the 1970s.

These tests were conducted before the women were allowed entry into Britain. In order to check whether their claims of being fiancés of British residents were true.

DESIblitz explores this dark forgotten past of Britain’s immigration policy.

The 1979 Guardian Article

On February 1st, 1979 journalist Melanie Phillips published an article in The Guardian which outlined one Indian woman’s experience of arriving at Heathrow Airport.

The article, which was front-page news, explained that a 35-year-old Indian woman arrived in Britain wishing to marry her fiancé, a British resident of Indian descent.

However, the immigration officers at Heathrow Airport suspected, due to her age, the woman was lying about being a fiancé. They believed she was already married and had children.

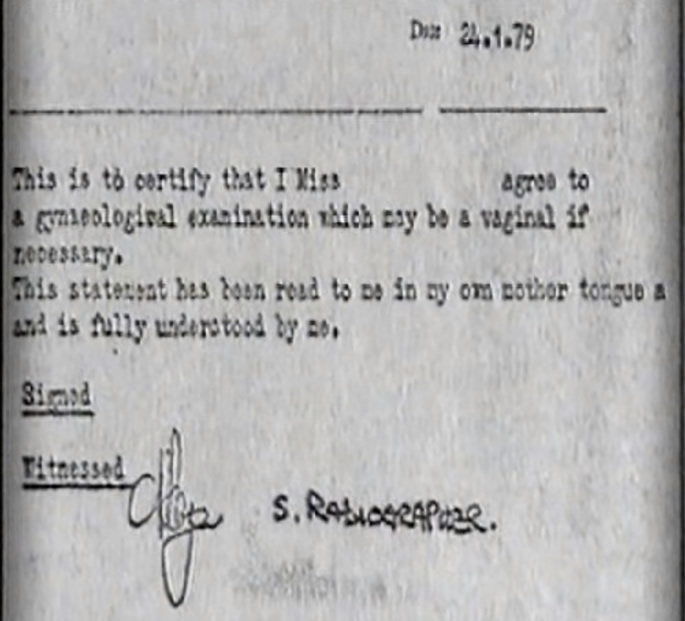

Due to this suspicion, a male doctor then proceeded to carry out a gynaecological examination on the woman.

This was done in order to prove whether she was a genuine wife-to-be, who had not had any children and was still a virgin.

Within The Guardian article, Phillips cited the woman who described the procedure:

“He was wearing rubber gloves and took some medicine out of the tube and put it on some cotton and inserted it into me.

“He said he was deciding whether I was pregnant before. I said that he could see that without doing anything to me, but he said there was no need to get shy.”

The woman told Phillips that she had only consented to the test because she was worried she would be sent back if she did not cooperate.

After the test, she was granted conditional leave to Britain.

This was the first time any such incident was reported.

Why was this woman subjected to this invasive test?

As the post-war years progressed there began to be a public backlash against coloured immigrants, this subsequently led to stricter immigration laws.

Prior to the 1970s, the South Asian immigrants within Britain were overwhelmingly male.

Academics, Evan Smith, and Marinella Marmo published an article in 2011 discussing the virginity tests of the 1970s.

They expressed:

“From the 1950s to the 1970s, the gender imbalance in migrant communities, where young men greatly outnumbered women, was viewed by some within government, the press, and anti-immigration groups as problematic, for it presented the danger of interracial relationships and mixed marriages.”

Further stating:

“It has been well documented elsewhere that fears of non-white migrants as sexual predators and of interracial relationships were prevalent among white British society throughout the post-war era.”

This fear and others led to the restriction of migrants coming to Britain for labour in 1962, under the Commonwealth Immigrants Act.

Also, this fear led to the Immigration Act of 1971. This act allowed “those classifiable as female family members”, such as wives, children, and fiancés to join their male family members.

The Immigration Act of 1971 also stated that women who were fiancés to migrant men living in Britain were allowed into Britain without a visa.

This was under the condition that they got married within the first 3 months of arriving.

It was under this act that the Indian woman, reported by Phillips, was tested upon her arrival in Britain as she was believed to be already married and lying to avoid the long visa process.

While the practice of virginity tests on migrant women was not explicitly allowed by law.

It was at the discretion of the individual immigration officer to test the woman under the loose term “medical examination” if they believed she was not a “genuine fiancé”.

The Aftermath and Public Outrage

The 1979 Guardian article caused a great deal of public outrage and government scrutiny.

A 2011 Guardian article asserted:

“The Guardian’s exclusive disclosure of the tests led to front-page stories in every leading Indian newspaper, with the incident denounced as ‘an outrageous indignity’ and ‘tantamount to rape’.”

The immediate public debate began over whether this 35-year-old woman’s horrific experience was an isolated case or in fact a recurrent immigration practice.

Due to the widespread outrage and government scrutiny, the government remained extremely elusive on this topic.

Within the days following the Guardian article, the Home Office denied that virginity tests were routinely part of the British immigration policy.

Contrary to what the Indian woman told the Guardian in February 1979, the Home Office also denied that they conducted any type of internal examination.

A recently discovered Home Office document, dating 1st February 1979, detailed the doctor’s side of the story:

“Penetration of about half an inch made it apparent that she had an intact hymen and no other internal examination was made.”

The British government sought to bury all discussion of this topic, therefore, did not explicitly provide information on how widespread the testing was.

However, on 19th February 1979, Home Security Merlyn Rees claimed that:

“a vaginal examination…may have been made only once or twice during the past eight years, according to records which have been looked at.”

Rees’ statement failed to take into account the incidents conducted by the British High Commissions in South Asia.

Following the article, there began to be speculation that virginity tests were also conducted offshore on South Asian migrant women.

Former Home Office Minister of State, Alex Lyon, admitted that:

“He knew that between 1974 and 1976 such gynaecological examinations had been performed in Dacca, where many potential migrants to Britain sought entry certificates.”

Further declaring:

“They did it fairly frequently in Dacca to discover whether a woman was or was not a virgin when she was claiming to be a wife.”

This was further confirmed in the House of Commons by Labour MP Jo Richardson.

She revealed that “at least 34 cases of virginity testing had been undertaken at the British High Commission” in South Asia.

Following the public outrage, Rees disclosed that Sir Henry Yellowlees, the Chief Medical Officer, would carry out an investigation into the virginity testing.

Smith and Marmo revealed that this action:

“was seen by critics – in parliament, the media and the black communities to be an attempt to stem further criticism of the government in the lead up to the 1979 general election.”

Due to this, the Commission for Racial Equality (CRE) also “pushed for an independent investigation of immigration control procedures and suspected racial discrimination within the immigration control system.”

In the weeks following Philips’ Guardian article, the horrendous treatment of South Asian migrants was raised before the United Nations Commission on Human Rights.

An Indian representative at the United Nations Commission on Human Rights stated on 23rd February 1979 that:

“The United Kingdom authorities systematically discouraged immigrants from the Indian subcontinent and employed immigration practises that seemed to reflect prejudices dating back to the dark ages.”

This condemnation was further supported by the Syrian Arab Republic representative who asserted the invasive practices:

“reflected the persistence of racism and colonialism in a disguised form.”

The Syrian Arab Republic representative also stated the practice was “an insult to the dignity of women in general and Asian women in particular.”

Once again, the British government remained elusive on how regular this practice was and tried to downplay the seriousness of the incidents.

Within Smith and Marmo’s article, they explained that:

“The British representative expressed ‘deep regret’ to the Indian government over the incident, but insisted that ‘no element of racial discrimination was involved’.

“The British representative acknowledged that the incident at Heathrow ‘should not have taken place’, but claimed that ‘it did not constitute a systematic abuse of human rights by the United Kingdom government’.”

Instead of issuing a formal apology that acknowledged the frequency of virginity testing, the British government tried to push attention to the apartheid and the killing fields of Cambodia.

Smith and Marmo suggest a reason for Britain’s downplaying and the “vague and elusive apology”.

They explain that this issue being made public and brought up by the UN created a sense of uneasiness for the British government. As Britain:

“Aiming to be portrayed within the international community as a champion of human rights…the Home Office had to concede that at least one virginity test occurred.”

Smith and Marmo further explain that this uneasiness and elusiveness was down to Britain’s previous position as a colonial power.

They expressed that the:

“colonialist-racist attitudes was raised [within the UN] by the very community that Britain has once occupied and ‘civilised’ before the international community that Britain desired to dominate.”

After it became public knowledge in February 1979, the government ensured that the practice of virginity testing would be terminated.

While the practice was stopped, according to Smith and Marmo’s 2011 article, a proper apology from the British government has never been issued.

After admitting to 2-3 cases in the United Kingdom and 34 cases in South Asia, the British government sought to bury all discussion of this topic.

No further information was released on the frequency of the testing after the initial public outrage in 1979. The true extent of this horrific testing was not revealed for another 32 years.

In 2011, researchers Smith and Marmo unearthed Home Office records within the National Archives.

Within a 2014 blog by the University of Oxford, they stated that:

“In 2011, we [Smith & Marmo] published research, based on the available documents at the time, which showed that the successor government under Margaret Thatcher knew that there were at least 80 cases.”

However, Smith and Marmo believed this to be only the tip of the iceberg.

In 2014 they published the book Race, Gender and the Body in British Immigration Control. The book explores the treatment of South Asian women by immigration control.

Within the blog by the University of Oxford, they stated that:

“As Race, Gender and the Body in British Immigration Control shows, after we found more relevant files in 2012 and 2013, that by 1980, the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) had uncovered many more instances – between 123 and 143 overall.”

Further expressing:

“A revision of the initial figure of 34 cases was never given by the Thatcher government and those in the Home Office and the FCO sought to bury any discussion of the topic after the initial public interest in 1979.”

The government’s attempts to deny and limit what the public knew about the cases just goes to show they knew it ‘was a gross violation of human rights’ despite denying it.

Sexist and Racist Justifications

However, these facts still do not explain why a woman’s sexual history has any correlation with obtaining permission into Britain.

The virginity test practice was not just a British immigration policy test to test a woman’s truthfulness. They reveal far more about South Asian women’s values in 1970s Britain and the continuation of colonial attitudes.

Smith and Marmo discussed Rachel Hall’s 2002 study on British immigration control. They used her information in relation to South Asian women:

“Those who enter the system of British immigration control are simultaneously categorised by the immigration authorities on the basis of their gender and ethnic membership.”

This is certainly the case in regards to the virginity testing of the 1970s.

A 2011 Guardian article on these virginity tests by Huma Qureshi states the story of Qureshi’s mother, who was also subjected to a virginity test.

Qureshi’s mother explained that she was unsure why they did the test, but she went along with it at the time.

When discussing the reasons behind the test she expressed:

“Maybe it was the colour of my skin and where I came from.

“They didn’t do it to the women coming from Europe or Australia or America, did they?”

She added:

“I suppose it was just to prove that they had power in their hands.”

Smith and Marmo asserted within their 2011 article that:

“This testing was not conducted upon these migrants solely because they were women, but because they were women of a particular ethnicity.”

The British government justified their action of carrying out virginity tests on the age-old generalisation that all South Asian women are virgins before marriage.

Therefore, believed they could prove if a woman was lying about being a fiancé.

On 9th March 1979, David Stephen, a Foreign and Commonwealth Office advisor, issued a report in which he reiterated this thinking:

“There is a logic in the use of these procedures since the immigration rules require dependent girls [as children, not wives] to be unmarried, and fiancées do not need entry certificates while wives do.

“If immigration or entry certificate officers suspect that a girl claiming to be an unmarried dependent is in fact married, or if a woman arriving at London Airport and claiming to be a fiancée of a man resident here is in fact a wife seeking to join her husband and avoid the ‘queue’ for an entry certificate, they have on occasion sought a medical view on whether or not the woman concerned had borne children, it being a reasonable assumption that an unmarried woman in the sub-continent would be a virgin.”

The only reason these women were subjected to the degrading procedure was because of the “reasonable” ethnic stereotype of all South Asian women being virgins before marriage.

Philippa Levine, within her 2006 study ‘Sexuality and Empire’, asserted that this assumption was based on the effects of Britain’s colonial past. She disclosed that this pointed:

“In a vivid manner, to how ideas and assumptions about colonial sexuality found expression in Britain.

“Examples such as this not only demonstrate the effects of the colonial past within Britain but also reveal just how central a role sexuality has played in shaping that complex legacy.”

South Asian women were assumed to be the stereotypical meek, traditional, and subordinated wives. This concept of the submissive South Asian woman was widespread amongst the British in colonial India.

Antoinette Burton, in her 1994 book Burdens of History: British Feminists, Indian Women, and Imperial Culture, explained that the British men viewed the Indian woman as:

“helpless, degraded victim of religious custom and uncivilized practices.”

It is for this reason why British men favoured relationships with South Asian women in colonial India, as they were viewed as obedient to men.

It is this very thinking that was reflected in the British immigration policy’s actions.

Smith and Marmo, speaking on South Asian women’s status in British society, asserted:

“Unlike migrant men who were deemed to have an immediate economic value as skilled or unskilled labour, migrant women from the Indian subcontinent were seen by the British government as having no value in the labour market.

“Their social and economic value was determined only by the use of their female bodies, primarily in relation to other (non-white) men.”

South Asian women were determined by their bodies right from their first step into Britain. Smith and Marmo further expressed:

“To enter Britain legally, the female migrant had to acknowledge the subordination of her position in British society and subject herself to the assumed knowledge and prejudices of the British authorities.”

South Asian women were scrutinised by Immigration officials in the 1970s if their bodies did not fit into the generalised bracket.

It is rather ironic that this was considered a reasonable justification to carry out virginity tests considering the 1970s British social and cultural climate.

In 1979 the Commission for Racial Equality and the Equal Opportunities Commission were both highly critical of the dehumanising practice.

Betty Lockwood, the Chair at the Equal Opportunities Commission, expressed within a letter to Merlyn Rees that the practice was:

“nothing short of victimisation of women…which we would have thought totally alien to our national attitude and way of life.”

Lockwood’s latter point does raise an interesting point of discussion. As it is ironic that these were the justifications behind conducting virginity tests, considering the changing 1970s British “national attitude and way of life”.

Between the ’60s and ’70s, Britain witnessed a systematic shift in attitudes towards sex and sexuality. The period has often been referred to as the sexual revolution, a time that witnessed more liberal attitudes towards sex.

19th-century British society placed a huge emphasis on a woman’s chastity and modesty.

A 2013 article by the British Library stated that:

“Sexual intercourse was presented, for women, as something that occurred within a heterosexual marriage, for the sole purpose of procreation (conceiving children).”

However, the sexual revolution of the 60s and 70s brought greater sexual freedom for women.

It was commonly thought to be brought about by the introduction of the contraceptive pill and the legalisation of abortion in 1967.

Along with this sexual freedom, there was a greater emphasis on sexual pleasure for women.

Therefore, considering this sexually liberal climate of 1970s Britain, it is rather contradictory and racially absurd that South Asian women were subjected to the trauma of virginity tests.

Just because of an age-old prejudice that did not apply to wider 1970s British society.

The virginity test cases prove the power the British government had over immigrants. It also proves that there was a very fine line between government procedures and abuse, in regards to immigration.

Violation of Human Rights

The fact these tests were only conducted on South Asian women harps on the deep-seated imperial sexist and racist prejudices and attitudes.

As if the tables were turned and white British women were being forced to prove their virginity then the reaction and apology would be very different.

It is easy to solely focus on the racial motivations behind these cases, considering the wider backlash against coloured immigrants in the post-War years.

However, this would lead you to forget that actual women had to undergo a degrading test.

Qureshi’s mother, within the Guardian article, recalled:

“You forget about things when you start a new life.

“But when I think about it now, it was a violation of my rights.”

One can only imagine how humiliating and degrading this was for a woman’s first experience in Britain. These women were at one of the most vulnerable stages in their lives.

They often travelled to Britain alone with no family.

They were coming into a new country, a new society with a new language, a new culture – and their first encounter in Britain was an invasive humiliating test of their body by a stranger.

The official Home Office records never included the names of the women being tested. This highlights how the South Asian women were just viewed as “bodies” and not people by the British immigration policy.

The women were not just subjected to physical violation, but also moral and mental violation.

The fact there were no names associated with the records raises the question of consent, as no written consent was given.

This then raises another point that, if given, how genuine would the verbal consent have been and to what extent was it forced consent from already vulnerable women.

The women, who had legally come to the UK, were preyed on and underwent sexual abuse just because British immigration officers had the right to at the time.

It can be difficult to discuss this dark and forgotten period of Britain’s immigration policy. The period was deep-seated in age-long colonialist racial prejudices, as well as a period that witnessed a major human violation.

As Smith and Marmo suggested, this is just the tip of the iceberg. Due to the government’s concealment of information and researchers only recently discovering more cases, the virginity tests controversy still requires further investigation.