"For the first time, people saw me as Asian."

Many US and UK Asians feel confused about finding their identity.

Whether you originate from East or South Asia, people are unsure whether to conform to western standards or remain true to their culture.

However, the West has created its own definitions of being Asian that aren’t as simple as geography anymore.

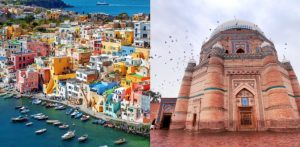

This takes the form of an East Asian emphasis in the US and a South Asian focus in the UK.

But why the difference? After all, isn’t Asia just a continent?

Empires, alliances and migration paths are all part of the historical reasons for why ‘Asians’ refer to different communities in the west.

Although, this sub-categorising creates a division between the collective Asian community, which is becoming more prominent than ever.

DESIblitz uncovers how these contrasting definitions have come to be, through the lens of history.

The Definitions of Being Asian

The word ‘Asian’ would usually lead to some geographical location.

The United Nations determines Asia as having 48 countries and the Census Bureau defines a person of the Asian race as:

“Having origins in any of the original peoples of the Far East, Southeast Asia, or the Indian subcontinent.

“Including, for example, Cambodia, China, India, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Pakistan, the Philippine Islands, Thailand, and Vietnam.”

Often based on population prominence, Asian definitions differ within the western globe.

When asking a Brit, the word ‘Asian’ usually refers to the South Asian community.

Despite South Asia’s basis across eight countries, Brits are often referring to the Indian and Pakistani communities here.

The reason for this is, on the surface, is the prevalence of these populations in the UK. India topped the non-UK countries of birth for the United Kingdom in 2011.

With an Indian-originating population of 722,000, the sheer numbers could justify the South Asian emphasis in the UK.

Pakistan and Bangladesh rank third and sixth on the non-UK born resident’s statistics, respectively.

However, the disassociation experienced by the remaining Asian population is arguably also proved by the statistics.

Within the same non-UK born data collection, China ranked 10th on the list. It was the only East Asian country to feature on the Office for National Statistics graph.

Although, the American counterparts often possess a contradicting perception of Asians.

A mention of the Asian population in the USA initiates thoughts of the East Asian community.

East Asia consists of China, Japan, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea, and Taiwan. China, North Korea, South Korea and Taiwan.

However, the reasoning for the East Asian emphasis in the US can’t be simply explained by population value.

When locating the dominant Asian populations in the US, East Asian countries do not necessarily prevail at the top.

According to a 2021 report, Pew Research found that China dominates 24% of the American-Asian population, whilst India is second (21%).

South-East Asian countries also hold notable hubs in the American-Asian population.

More specifically, the Philippines (19%) and Vietnam (10%) make up a considerable part of the figures.

However, the report also emphasised the smaller percentages of East Asian collectives, such as Korea (9%) and Japan (7%).

So why is this East Asian labelling not as reliant on population growth in the US?

Moreover, why have South Asians always taken the forefront in British Asian judgments?

The Historical Reasoning for Asian Divisions

The British Empire is undeniably a reason for these definitions. British Imperialism centred heavily around South Asian countries.

India, Bangladesh and Pakistan were all under British rule, emphasising the links between these countries and Britain.

For example, military connections were made between countries in the British Empire.

A Striking Women article highlighted:

“Sikh soldiers who served in elite regiments, were often sent to other colonies of the British Empire, and saw active service in both world wars.”

Furthermore, the rise in South Asian migration to Britain shaped population diversity.

From labour shortages to ambitions of starting a new life in the west, South Asian migration thrived in the 1960s.

In contrast, the US did not mirror these patterns. However, the importance of war allies did influence East Asian prominence.

The rising rivalries within the Cold War allowed Americans to become updated on their Asian counterparts.

Lynne Murphy, a linguistics professor at the University of Sussex explains:

“The US was at war with Japan, then Korea, then Vietnam, and has occupied other parts.”

The American involvement in Asian conflicts posed the US as a reliable and favourable ally for East Asians. This would have somewhat encouraged migration to the west.

A 2014 Pew Research article deliberated:

“Whatever feelings Asians harbour about each other, most are likely to view the United States as the country they can rely on as a dependable ally in the future.

“Publics in eight of 11 Asian nations surveyed – including South Korea (68%) Japan (62%) and India (33%) – pick Uncle Sam as their number one international partner.”

So these differing migration and alliance patterns have formulated the Asian definition in the west.

The Confusion for Asians

Bridging the gap between Asians is essential in helping minorities to thrive in the western world.

The global differing definitions of US and UK Asians has created confusion and division.

The heightened recognition of certain groups in the west has generated a divide between the collective term ‘Asian’.

If we are sub-categorising this continental region, this gives rise to the individual complexity of belonging.

Identity confusion especially affects those who belong to two Asian heritages.

Claude Steele, Steven Spencer and Joshua Aronson define social identity threat as:

“The threat that people experience in situations where they feel devalued on the basis of a social identity.”

Kim Singh is a British Indian-Thai who has experienced the UK’s lack of consideration towards a variety of Asian ethnicities.

Recalling her experience in filling out medical forms, she expresses:

“When I fill in the ethnic group section on the form I’ve always put Indian without hesitation – just because I’ve grown without my [Thai] mother figure.”

However, she considers how other mixed ethnicity Brits would encounter further issues:

“I feel like other mixed people would’ve probably had more of an identity crisis if they were living with both parents.”

Growing up in an environment that encounters two Asian backgrounds can lead to cultural imbalances.

This is particularly relevant if the west has focused on some Asian cultures more than others.

Kim developed on the lack of identity inclusivity on certain forms:

“They only label a few South Asian ethnicities like Indian, Pakistani etc.

“Then Chinese is placed in another subheading usually, and it’s the only East Asian country listed.”

She then went on to reconsider the lack of representation of the rest of the Asian continent:

“The entire rest of Asia is disregarded completely if you’re not from those three countries.”

However, the identity trouble produced by forms isn’t something applicable to the UK alone.

A TIME article recalls a forum that imposed the question – “Do Indians count as Asians?”

The article continues to note a 2016 study by the National Asian American Survey which astonishingly revealed:

“42% of white Americans believed that Indians are ‘not likely to be’ Asian or Asian American.”

“With 45% believing that Pakistanis ‘not likely to be’ Asian or Asian American.”

Even more surprisingly, the survey also concluded:

“27% of Asian Americans believed that Pakistani people are ‘not likely to be’ Asian or Asian American with 15% reporting that Indians are ‘not likely to be’ either.”

The fact that these nationalities are even considered to be non-Asian exemplifies the reality of this dissociation and divide.

Seema Hassan* is a Pakistani student who was born in California but now resides in Leeds.

She highlights the two essences of the ‘Asian’ definition and how she was conflicted about her own identity because of this:

“Growing up, classmates would ask me ‘what are you’ and I would just say ‘I’m Asian’.

“They would always disagree and tell me that if I’m Asian, why don’t I look Chinese. This happened more times than you can imagine.

“I was constantly confused as a young girl. Why would they tell me about my own identity?

“Then I just had to start saying I was Pakistani and then the comments started like ‘where’s that’ or ‘is that in India?’

“When I came to the UK, it was completely different. People asked me ‘what part of Asia are you from?’. I was shocked.

“For the first time, people saw me as Asian.”

Seema’s experiences aren’t just applicable to South Asians, but East Asian interactions are very similar to this.

The division of Asians created by societal mindsets has confused and developed invalidation for many.

There needs to be a significant and collective progression towards educating people about Asia and all the wonderful countries that make it up.

Reaching Out and Closing The Gap

The differences between Asians is not something that should be completely eradicated.

It is careless to ignore that Asians from different regions will have different experiences and values. However, we can bridge an unnecessary gap created by a lack of inclusivity.

Individuals in the 2020 American Presidential Race spoke out about a division of Asians in the elections.

Andrew Yang recounted his recognition of this disconnection:

“My Asian-ness is kind of obvious in a way that might not be true of Kamala or even Tulsi.”

“That’s not a choice. It’s just a fairly evident reality.”

So, closing the rift between the community can reunite the minority in the western world. It’s not impossible to close this gap either.

Asians have often been through similar struggles and encounters of having to integrate within a new society.

Cultures frequently transgress borders, from food to religion to language. US and UK Asians have also experienced collective pain and hatred too.

The Stop Asian Hate Movement peaked in 2021. Asians collectively demanded for hatred fuelled towards their communities to stop.

Although this surrounded more East Asians, it coincided with South Asian issues such as the farmers’ protest in India.

The most common definitions of being a US or UK Asian can often feel alienating. Not being fully recognised for your ethnicity can promote feelings of identity confusion.

That’s why we need to redefine the lack of inclusivity created by popular associations of Asians.

Being a minority in the western world can already be a hard experience.

Why create divisions within a society that has already struggled enough to feel like they belong?