"It's essential that we prepare our young people for that future."

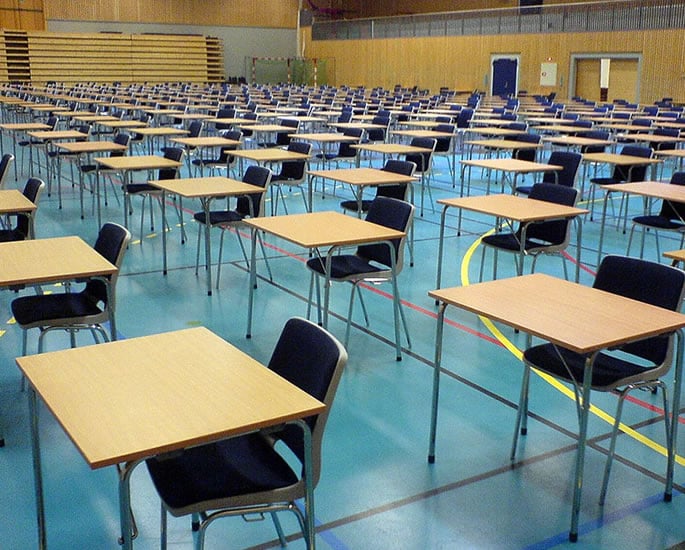

In the biggest shake-up of England’s education system in a decade, the government has announced plans to reduce the time students spend in GCSE exams by up to three hours.

This move is a central pillar of a wide-ranging curriculum review that has frankly labelled the current volume of testing “excessive”.

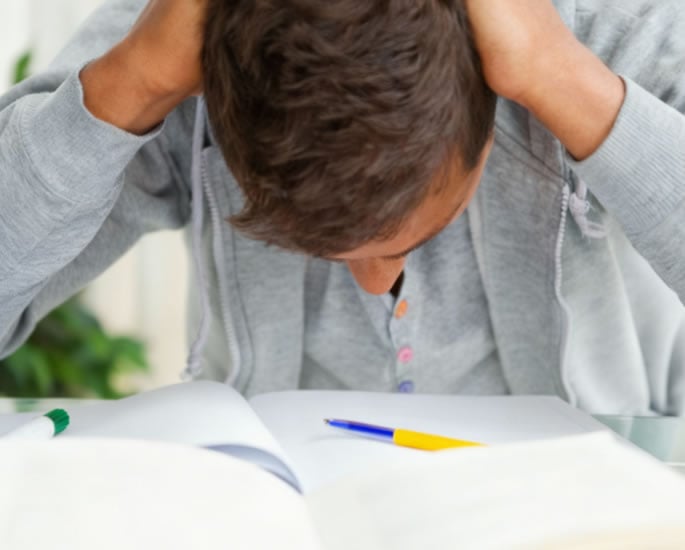

For parents, particularly within the British Asian community where educational attainment is highly valued, navigating the intense pressure of the exam period is a familiar challenge.

This announcement signals a shift in the approach to secondary school assessment, one that acknowledges the toll that high-stakes testing can take on young people’s mental health.

The changes, set to be rolled out from September 2028, aim not only to ease the burden on students but also to introduce new, relevant subjects to better prepare them for the modern world.

Here is what you need to know about this shake-up.

A ‘More Nuanced Approach’ to an ‘Excessive’ System

The core of the announcement is the 10% reduction in the overall volume of exams at Key Stage 4.

This isn’t a minor tweak; for the average student, it could mean up to three fewer hours spent in a silent exam hall.

The decision is a direct response to the findings of a curriculum and assessment review commissioned by Labour in 2024.

Professor Becky Francis, who led the review, put the issue in a global context, stating:

“We are an international outlier in the number of exams and the volume of exams we have aged 16, only Singapore is anywhere near us”.

This acknowledgement of “excessive” testing will resonate with many families who have witnessed the stress it can cause.

Recent statistics paint a stark picture: one survey found that 85% of UK students experience exam anxiety.

Teachers have also noted the impact, with 77% observing a rise in exam-related anxiety in their classrooms.

Professor Francis was clear that the goal is to bring down the “very intense and elongated time” of GCSEs without wanting to “trade standards and reliability.”

The Department for Education (DfE) will now work with the exam regulator Ofqual and exam boards to implement this reduction, aiming for a system that assesses knowledge without overwhelming students.

What Will Be Added to the Curriculum?

Alongside the reduction in exam time, the curriculum itself is set for its most significant update in over a decade.

Recognising that the world has changed profoundly, the reforms will introduce new subjects designed to equip students with practical and critical life skills.

For the first time, primary school children will be explicitly taught how to identify fake news and disinformation, a crucial skill in an age of digital saturation.

This will be complemented by a greater emphasis on financial literacy, covering the fundamentals of money to reflect that children are becoming consumers at an ever-younger age.

For older students, the reforms look towards the industries of the future.

The government is exploring a new qualification in data science and AI for 16 to 18-year-olds, a direct move to encourage more young people into careers in science and technology.

Education Secretary Bridget Phillipson emphasised the need for these changes:

“It’s been more than 10 years since the national curriculum was updated.”

“In that time, an awful lot has changed… It’s essential that we prepare our young people for that future.”

This focus on future-proofing the curriculum signals a move away from rote learning and towards skills that will be vital for the next generation’s success.

Scrapping EBacc

A hugely significant change for secondary schools is the decision to scrap the English Baccalaureate (EBacc) as a performance measure.

Introduced by then-Education Secretary Michael Gove in 2010, the EBacc measured the percentage of students taking a specific combination of “core” academic subjects: English, maths, science, a language, and a humanity.

While intended to raise academic standards, critics have long argued that it has had a narrowing effect on the curriculum.

The review’s final report stated bluntly that the measure had “unnecessarily constrained students’ choices,” which “affected their engagement and achievement, and limited their access to, and the time available for, arts and vocational subjects”.

Its removal is intended to give schools and students more flexibility.

In its place, there will be a new statutory entitlement for all GCSE pupils to study triple science. Previously, access to separate GCSEs in Biology, Chemistry, and Physics was often limited to the highest-achieving students in certain schools.

Making it a standard offering will open doors for more students to pursue STEM subjects at A-Level and beyond, providing a stronger foundation for those aspiring to careers in fields like medicine and engineering.

This move directly addresses the need for a scientifically skilled workforce while allowing students with passions in the arts and vocational areas to pursue them without penalty.

Building Confident Citizens

The reforms extend well beyond the GCSE years, reflecting a broader philosophy of educating the whole child.

New compulsory tests in maths and English will be introduced in Year 8, designed not as high-stakes assessments, but as tools to help teachers identify and address learning gaps sooner.

Similarly, the controversial Key Stage 2 grammar, punctuation, and spelling test will be overhauled to focus more on the practical application of grammar in writing, rather than the memorisation of complex terms like “fronted adverbials.”

Furthermore, the government is committed to broadening pupils’ experiences.

Citizenship will become a compulsory subject in primary schools, ensuring all children learn about democracy, financial literacy, and climate education.

An oracy framework will be published to help young people become more confident and effective speakers, and an entitlement to enrichment activities, spanning the arts, sports, and outdoor education, will be benchmarked and inspected by Ofsted.

This suite of changes points to a more holistic vision for education, one that values critical thinking, confident communication, and real-world skills alongside academic achievement.

Parents anxious about a sudden upheaval can be reassured that these changes will be phased in gradually.

The government has stressed that it does not want to “rush” the implementation.

As Education Secretary Bridget Phillipson stated:

“We want to get it right, so the programmes of study will be out for consultation by 2027 – and the national curriculum will be taught by 2030.”

The revised curriculum is expected to be published by spring 2027, with the first teaching set to begin in September 2028.

This deliberate timeline provides schools and teachers with the necessary time to prepare for the new curriculum and assessment methods, ensuring a smooth transition for students.

The government’s announcement represents a landmark shift in educational policy.

The headline reduction in GCSE exam time will be welcomed by the many parents, students, and teachers who have long felt the strain of an overloaded and high-pressure system.

However, the reforms go much deeper, seeking to create a more balanced, modern, and holistic curriculum.

By removing the constraints of the EBacc, introducing future-focused subjects, and embedding skills like oracy and critical thinking from a young age, these changes aim to equip the next generation for the challenges and opportunities of the 21st century.