"Feminism struggles with the knowledge of sexual desire"

Within the diverse fabric of India, conversations concerning women’s sexuality frequently find themselves cloaked in layers of social stigma.

However, amid these intricate constructs, figures are trying to break through the silence.

Among these luminaries stands Amrita Narayan, a renowned clinical psychologist and psychoanalyst.

With a notable repertoire including her role as the editor of The Parrots of Desire: 3000 Years of Erotica in India, Amrita Narayan has carved a niche for herself.

Now, in her latest endeavour, Women’s Sexuality and Modern India, Amrita ventures into uncharted territory.

She meticulously unravels the intricate layers that cloak women’s sexuality in contemporary Indian society.

Through intimate interviews, glimpses into psychotherapy sessions, and insightful literary analysis, Amrita explores the deeply entrenched patriarchal structures that shape these experiences.

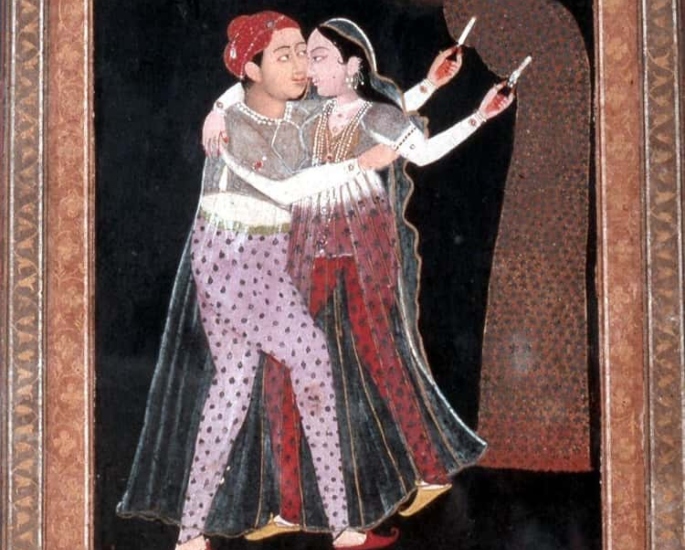

Historically, India has been both celebrated and critiqued for its portrayal of sexuality, with ancient texts such as the Kama Sutra offering glimpses into a more liberated past.

Against this backdrop, the exploration of women’s sexuality takes on added significance, catalysing societal dialogue and introspection.

By unpacking the complexities of female desire and agency, Amrita’s work challenges prevailing stereotypes and offers a platform for women to reclaim ownership of their bodies and identities.

So, DESIblitz chatted to Amrita to discuss a once-celebrated element of Indian culture and dive into her thoughts around such a concept.

Can you share some insights into female experiences of sex under patriarchy?

To write this book, I did 12 long-form interviews each between 10-30 hours.

During these interviews, I asked only one question: “tell me about your sexuality” after which I only prompted for more information.

The first six interviews were conducted in Ahmedabad, after which I did six more in Mumbai and Bangalore.

All the women were self-described middle class which means there is a good chance they were financially upper-middle class.

There were 10 Hindus, one Muslim, and one Christian woman and their birth years were 1950-1992.

They were all pretty educated, and this was partly the point because the educated middle and upper-middle-class woman is thought to be free of some of the problems that characterise sex under Indian patriarchy.

But I’m not sure that they are.

The book is full of the insights that I got from the interview excerpts and psychotherapy sessions, but maybe I can somewhat summarise them by reiterating the subtitle of my book: “In a Rapture of Distress”.

Some women are stuck in grieving the losses of patriarchy, some have glorified this grief, and some women gain pleasure from grief-stricken sexual experiences.

All of the women have to find pleasure (rapture) within a framework of distress because either they, or their mothers, sisters, or friends, have to sort out their sexuality within the distress that is patriarchy.

In what ways does the Indian patriarchy shape women’s sexuality?

Women born between 1950-1992, grew up in a culture of statistically documented boy-child preference, in which the control of girls’ sexuality was used to anchor the anxieties of the family and the community.

This was a highly gendered, binary world in which real men and women functioned symbolically as part of a unified psyche whose anxieties were infused into and enacted upon women’s bodies.

My book explores numerous examples of the effects of this impingement of the cultural into the personal.

“Not everyone experiences this impingement as a trauma.”

But many women do find their sexual confidence affected by the way patriarchy rewards them for being sexually innocent and punishes them for being sexual agents.

Some find that the heaviness of being part of the cultural body creates an obstacle to sexual levity and lightness.

Some find that various forms of masquerade – for example, docility in public and aggression in private – help them get out of the weight of the cultural body.

Many women have experienced self-hate for normal sexual aggression because sexual aggression has historically not been supported for women as it has for men.

Overall, the question of how to acquire sexual confidence is beleaguered by conflict.

Women don’t feel fully individual in their sexuality. The presence of the family in their psyche is almost a form of part ownership – especially an ownership of daughters by mothers.

Thus the presence of an unspoken dialogue with the mother in women’s inner worlds is a natural continuation of a patriarchal upbringing.

Can you discuss the role of the mother-daughter relationships?

Empirical studies in psychology tell us that worldwide – not just in India – mothers are charged with the task of socialising their daughters in sexuality.

Aside from physical labour – which mothers already do more than fathers – mothers have the psychological labour of ensuring their daughters conform to the sexual dynamics of patriarchy whatever these look like in their local culture.

Mothers do this to different extents and by different methods.

What the research in India shows is that the more the mother makes it clear that her daughter’s sexual control is her personal goal as well as a social goal, the harsher the method of policing the daughter’s sexuality.

The relationship between sexuality and mothering came up uncannily and unprompted in every single interview I did for this book.

Sexual norms of a previous generation are transmitted intergenerationally.

Women have to work through their unconscious loyalty to the sexual values of a previous generation whenever these values are at odds with their desires.

This unconscious loyalty to the sexual values of a previous generation can be expressed as imitation, self-hate, paralysis or in numerous other ways.

To get to freedom in sexuality is a painful route because it can be beset with loneliness and grief that goes with giving up the values – and corresponding intimacies – of a previous generation.

This does not mean that it is not worthwhile to pursue freedom, but rather to remember that it is not pure pleasure -it has a cost to it.

To become robust enough to bear that cost would be to grow up, but not everyone wants to grow up and I don’t think we should demand a unilateral version of sexual maturity.

Can you explain the power and competition within heterosexual relationships?

One of the points I belabour in my book is the absence of a father from the early life of children and the impact this has upon daughters born in India during the period 1950-1992.

The absence of fathers in early life creates anxiety around normal aggression towards men.

In the Indian family, empirical studies tell us that no one is allowed to express anger toward fathers.

“They also state mothers are in charge of enforcing this emotional socialisation.”

The missed opportunity to express anger safely with a man in early family life gives women a power disadvantage in heterosexual relationships.

When it comes to sexual desire, this concern of early life gets interpreted in diverse ways – some women are compliant with their male partners, others find a way to be playful with their angry feelings, and others choose to exercise sexual revenge upon men.

There is no template solution, but the problem of this power dynamic – that has its history in the patriarchal family – is always present.

As a power dynamic, heterosexuality is founded upon losses and absences – the loss of the father from early life and the loss of the homoerotic companionship of the mother.

How does society contribute to the preservation of heterosexuality within Indian society?

Most of the sexuality explored in my book is heterosexual desire, yet many of the women I spoke with – especially one of the oldest women – spoke with sadness about their lost chance to express homosexuality.

Considering that the Supreme Court recently ruled against homosexual marriage, the social pressure for heterosexuality in India is pretty explicit.

The patriarchal structure of desire depends on the image of the heterosexual couple.

For men to overcome their vulnerability of being born to women, a heterosexual couple has to be enshrined as the image of patriarchal control of women.

Since homosexuality fails to connote the patriarchal message of “man dominates woman” it has to be kept out of visibility.

But what I focus on in my book is less explicit homosexuality – except when the interviewees bring it up – but the ubiquitous nature of repressed female homoeroticism.

The empirical truth – that mothers worldwide suppress their daughter’s sexuality, is rife with homosexual violence.

To follow through, the mother has to violently overlook her normal oedipal attraction for her daughter, and push her daughter towards heterosexuality and the aesthetics of being an object for men.

Maternal violence towards daughters who defy the patriarchal sexual norm gains their energy from the pain of the mother’s own violently repudiated sexuality, especially her homoerotic feelings towards her daughters which have to be annihilated for her to push them to controlled heterosexuality.

How do you navigate feminism and patriarchy when considering women’s desires?

Too often women’s desires for both patriarchal and ‘liberated’ sexual experiences are navigated by self-hate (“how terrible of me to want this”) and confusion ( “how could I possibly want what I want?”).

One of the things I try to explain is that desire pulls upon women’s loyalty in diverse ways that defy logic but that have an unconscious process to them.

So for example we may be remembering or working out our patriarchal upbringings through the dynamics of adult desire.

“The idea is that we can replace self-hate and confusion with meaning.”

Given that it is a struggle for so many women to desire freely at all, it’s worth cultivating non-judgement in matters of sexual desire even if it’s simply in the service of self-knowledge.

Feminism struggles with the knowledge of sexual desire because feminist politics depend on the idea of women’s cohesive desire for liberation.

Many of the women I spoke with described feminism as legislating their sexuality, doubling down on what patriarchy is already doing but from a different direction.

I’m not saying that feminism should abandon its political fight for women to desire better, less patriarchal, experiences.

But if we are to think of a feminism that includes tradition and modernity and women of different generations and geographies, we need to accept that there is an ambivalence in the political struggle against patriarchy when it comes to matters of sexual desire.

I think we should navigate that ambivalence with compassion.

What influences sexual liberation in different geographical contexts?

Implicit in the discussions of geography in my book is the idea that every country has its sexual aesthetic preferences: how its culture thinks sexuality ideally is or ought to be.

Unstated yet legible, the preferred sexual aesthetics of cultures can be read via their aesthetic products – in literature and film – and also via the gaze they extended towards the sexuality of other countries.

Everybody is interested in the sexual aesthetics of other cultures: it’s the reason a Netflix series like Indian Matchmaker is as internationally popular as Emily in Paris is in India.

The problem is that cultures have different degrees of political and economic power which makes a culture’s sexual aesthetics into politics.

Cultural forces suppress women’s sexuality: this is an empirical fact, well-documented by the analysis of the psychologists Baumeister and Twenge.

In 2002, when these researchers analysed cross-cultural studies, they found that the psychological phenomenon of women’s sexual suppression is produced by three factors internalised by women.

These are imagined negative gossip, concerns about reputation, and memories of maternal socialisation – what and how girls learned about their sexuality from their mothers.

The researchers concluded that women’s sexuality was more suppressed in countries (like India) which have not had a public sexual revolution.

While I think the nature of suppression varies by culture, I do think that growing up or being parented by someone with a non-sexual revolution has an enormous bearing on the kind of sexual subject you become.

I think my book offers a kind of looking glass for this subject, whereas feminist sexuality is generally looked at through the lens of post-sexual revolution countries

Can you tell us about the secret sexual agency?

Secrecy and double lives show us how libidinous women manage the fact that they are under sexual control – by following the letter of the law but not the spirit.

I spoke with many women who had long-term sexual relationships outside of their marriages, which they kept a closely guarded secret.

These women led carefully constructed double lives, following their prescribed roles on the surface and nurturing erotic lives that were private to their public and familial roles.

Sexual pleasure achieved in secret requires quite a bit of agency and inner strength and is probably the oldest method of getting out of the patriarchal control of women’s sexuality.

“I realise that in western modernity this is considered hypocritical.”

So it’s perhaps worth emphasising that for some of these women, their double lives were perfectly acceptable if not always comfortable.

There was not necessarily a dream of eventually “coming out” into the open, which is perhaps a common dream in post-sexual revolution cultures.

Yet before the sexual revolution – whose central values are democracy and openness – the secrecy and double lives solution was quite common worldwide for women as well as for homosexual men.

If we want to include all geographies in sex-positive feminism, we might need to take a look at the idea of the visibility of sexuality as being universally desirable.

It might be less a universal desire and more a cultural value that has a meaning within the time period of a culture, not a universal meaning.

Could you elaborate on the concept of a “curious spectatorship”?

Curious spectatorship means pausing, rather than immediately crying “oppression!” when we see differences in matters of desire.

It means being imaginative about what women are getting out of it (the patriarchal setup) instead of insisting they get out of it (insisting that everyone be “liberated”).

Curious spectatorship towards non-sexual revolution countries means acknowledging that there is eros to living in a patriarchal family that competes with the eros derived from sexual freedom.

Thus to seek to be “free” is expensive, and women often seek unusual and imaginative ways of being free so they don’t pay too high a cost.

One story I tell in my book of uncurious spectatorship is the story of two American midwives who came to interview me in 2014 for assistance working with Indian women at a hospital in California.

The midwives had travelled to India to research a corrective to the practice of ‘scrooping’, a method of getting pregnancy that was very popular amongst the Indian female patients at their hospital.

In scrooping, women use their hands to insert their husband’s semen into their vagina rather than have sex with him.

The midwives’ research project was to help the women have sex with their husbands rather than support their getting pregnant via this unusual – though fairly widespread – method.

While the midwives’ desire for their patients to experience sexual intimacy was well-intentioned, I thought it was uncurious because it misses the opportunity to see what desires are getting satisfied via scrooping.

The women who were scrooping came from patriarchal family structures that grant a higher status to women who are mothers but can never support queer desire or divorce.

Curious spectatorship means acknowledging that scrooping might have diverse meanings that can include imaginatively gaming the system.

Getting pregnant without having sex allowed these women to gain status as mothers in the larger patriarchal family while preserving love objects in their minds.

Seen this way, the act of declining to have sex with their legal husbands and inseminating via scrooping takes on a whole new set of meanings.

Such curious spectatorship complicates the midwives’ plan of correcting the scrooping women to “normal” sex with their legally wedded husbands.

It also considers the scrooping women as having intelligence and making choices, not passive victims of oppression.

How do you address the complexities of women’s adaptations to patriarchy?

Rather than addressing this complexity, I think my book offers a framework for understanding complexity.

Since women sometimes gain pleasure and oppression from the same location, I suggest we can be of service to women by allowing them the complexity of choosing which oppression they want to liberate themselves from, and which oppression gives them pleasure.

“That means instead of demanding consistency, we might need to exercise curiosity.”

This may allow for sexual desire that goes outside of values and indeed out of character.

For all of us, the task is perhaps to grow from being babies who need women to be consistent characters, to becoming adults who understand that it is complexity and difference that makes women the characters they are.

How do you see your work contributing to broader conversations within feminism?

Perhaps the central contribution I hoped to make in this work was to construct sex-positivity in broader terms that include non-sexual revolution countries.

To decouple liberation from the conventional optics of the post-sexual revolution western world means to make visible both the struggles and the choices of women who live less optically evident sexual lives.

The tendency is to suggest that everyone should work towards the post-sexual revolution model of optically evident and freely available sexuality.

But it’s worth having a broader conversation about where free supply, democracy, clarity and obviousness in sexuality will take us.

While it is tempting to suggest that there is a “best version” of sexual freedom, I think it’s interesting to also ask questions about what is gained when individual advantages in sexuality are not made visibly apparent.

So instead of asking “how does everyone become free to have more sex?” we could study questions such as:

- Do women live at greater peace with each other when their sexual competitiveness is less explicit?

- Are imaginary lovers better or worse than real ones?

To ask more unusual questions would be to admit that no one culture has the answers and that the direction of learning about sexuality can perhaps go both ways instead of linearly.

We might still decide that the majority of people would like to be free to make choices about their sexuality.

But the process by which we go about this would be inclusive of the truth about other forms of inequality.

Another conversation I hoped to contribute to is it’s important to make room for the idea that there are no universals in distress, and being capacious and curious may be difficult and important in how we construct “liberation”.

Feminism – and I count myself as a feminist – needs to consider that while the women’s movement draws strength from a feeling of being united in common distress, every individual and culture has unique elements to what is considered distressing.

I wonder if we can think of feminism beyond struggle and distress or at least to add to the distress, the possibilities of pleasure and rapture.

Lastly, psychoanalysis itself has historically emphasised a very linear route to the liberation of repressed sexuality via a process of mourning, the proverbial “remembering, repeating and working through”.

It’s important to consider that not everyone wants to “work through” their desires into a better, healthier sexuality we may be domesticating desire by assuming there is a best or ideal “clean” version of having it.

Amrita Narayan emerges as a steadfast advocate for the empowerment and emancipation of women in the realm of sexuality.

Through her nuanced analysis and empathetic storytelling, she invites readers on a journey of introspection and discovery.

By breaking down the real stories of women’s sexuality in India, she urges us to confront the uncomfortable truths that lie at the intersection of culture, psychology, and gender.

As India continues to grapple with shifting paradigms of identity and expression, Amrita’s work serves as a beacon of importance.

By amplifying the voices of women and challenging societal norms, she paves the way for a less stigmatic society.

Grab your copy of Women’s Sexuality and Modern India here.