"You're constantly aware that your choices aren't just yours."

The weight of expectation can be a heavy cloak. For many British Asians, it’s one stitched with threads of familial duty, cultural honour, and the silent sacrifices of immigrant parents.

Growing up, the desire to be the “good child” is often paramount. This means achieving academically, behaving impeccably, and embodying community values.

But what happens when the child becomes an adult, with their own aspirations and desires?

Does this deeply ingrained need for parental validation simply fade? Or does it linger, subtly (or overtly) shaping life choices, relationships, and ultimately, mental wellbeing?

We explore whether British Asians are still chasing parental approval in adulthood.

Roots of the ‘Good Child’

The concept of the “good child” in South Asian cultures is deeply embedded.

It isn’t merely about good behaviour; it’s intrinsically linked to ‘izzat‘ – family honour and prestige.

Actions of an individual, particularly a child, reflect directly on the entire family. This collectivist cultural framework often means prioritising group wellbeing over individual desires.

Many British Asian parents, often first or second-generation immigrants, made significant sacrifices. They left their homelands for a better future for their children.

This unspoken debt can create an environment where children feel a profound obligation to meet expectations.

Saima from Birmingham says: “You’re constantly aware that your choices aren’t just yours.

“It’s about upholding the family name, making them proud after all they’ve done.”

This sentiment is common. The desire to repay parental sacrifice through obedience and achievement becomes a powerful motivator.

Traditional family structures, where elders hold authority, further reinforce this dynamic.

Parental expectations, therefore, are not just suggestions but often perceived as duties.

Adulting Under Approval

As British Asians enter adulthood, the “good child” persona can persist.

The need for parental approval often extends into major life decisions. Career paths are a prominent example.

Traditionally, “approved” professions like medicine, law, or engineering are often favoured. Deviating from these can cause significant internal conflict and familial tension.

A 2021 Joblist survey showed 65% of respondents ended up in careers they felt their parents wanted. While not specific to British Asians, it highlights a broader trend of parental influence.

Marriage is another critical area. Parental approval of a partner, and the timing and nature of the marriage, remain significant.

London-based teacher Kamal explains: “Even though I’m financially independent, the thought of choosing a partner my parents wouldn’t approve of is incredibly daunting.”

This highlights a conflict between personal autonomy and deeply ingrained familial expectations.

The pressure isn’t always explicit; sometimes it’s an unspoken understanding, a desire not to disappoint.

This can lead to adults feeling their lives are on layaway, waiting for an approval that dictates their next move.

Impact of Constant Pleasing

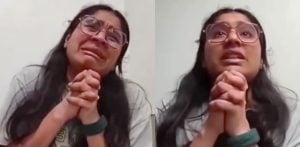

Constantly striving for validation carries a significant psychological burden. The fear of disappointing parents can lead to chronic stress, anxiety, and guilt.

Many British Asians experience a “clash” of cultures, where internal desires conflict with external expectations, leading to shame or guilt.

Psychologist Dr Anjali Sharma noted: “The pressure to be the ‘good child’ often means suppressing one’s true feelings and ambitions.

“This can lead to a fragmented sense of self and, in some cases, depression.”

Studies indicate South Asian communities may underutilise mental health services, partly due to stigma and fear of bringing shame upon the family.

The perceived need to maintain a perfect image can prevent individuals from seeking help.

This emotional suppression can manifest as anxiety, depression, or burnout.

Self-esteem can also be affected. When worth is tied to external approval, developing intrinsic self-worth becomes challenging.

The internal conflict of navigating dual identities – being British and Asian – adds another layer of complexity.

A Balanced Path

Breaking free from the “good child” complex doesn’t mean rejecting one’s family or heritage. It’s about recalibrating the relationship and finding a healthier equilibrium.

Setting boundaries is a crucial first step, though often difficult.

This isn’t about rebellion, but about protecting personal energy and autonomy.

As Rishi* says: “It took years, and many difficult conversations, to make my parents understand I could respect them and still make my own choices.”

Open communication, while challenging, is key. It involves expressing personal needs and perspectives respectfully, while also acknowledging parental feelings.

Redefining success and respecting parents on one’s own terms is also vital.

Success can encompass personal happiness and fulfilment, not just traditional markers.

Gratitude for parental sacrifices can exist alongside making different life choices.

Culturally sensitive therapy can be immensely beneficial.

Therapists who understand South Asian family dynamics can help individuals navigate these complexities, build self-esteem, and develop coping mechanisms. Many organisations now offer such specialised support.

Generational Shifts

There are signs that younger generations of British Asians are navigating these dynamics differently.

Increased exposure to Western individualistic values, coupled with greater access to information and support, may empower them to assert their identities more readily.

Millennials and Gen Z, globally, are often seen as prioritising work-life balance and personal wellbeing alongside traditional success metrics.

This shift may influence how they approach parental expectations.

The definition of “success” itself is evolving.

For many younger British Asians, it’s a more holistic concept encompassing mental health, personal growth, and societal impact.

This doesn’t necessarily mean a complete break from tradition, but rather a blending of values.

As sociologist Dr Aisha Khan comments: “We are seeing a gradual shift.

“While familial respect remains important, there’s a growing assertion of individual identity.

“The conversation is changing, albeit slowly.”

Parents, too, are part of this evolving dynamic. Some are adapting, recognising their adult children’s need for autonomy.

The hope is for relationships built on mutual respect and understanding, where love and approval aren’t solely conditional on fulfilling a prescribed role.

The desire for parental approval is a natural human instinct.

Within the British Asian context, it’s amplified by strong cultural values of respect, duty, and family honour.

While these values provide a rich sense of belonging and community, an over-reliance on external validation in adulthood can hinder personal growth and wellbeing.

The journey from “good child” to self-validated adult is complex and deeply personal

It involves introspection, courage, and often, challenging conversations. It’s about learning to honour one’s heritage and parents, while also honouring oneself.

Ultimately, the most meaningful approval comes from within, allowing British Asians to write their own unique success stories, rooted in tradition but not bound by it.

This fosters a future where familial bonds are strengthened by authenticity, not just obligation.