"Isn't that baby pretty, she's so light"

The quest for lighter skin is a common battle all around the world, and very common in the South Asian community.

Skin lightening products are marketed to all of those whose skin is darker than what the masses consider beautiful.

With these products being easily available in local shops, the high street and online, it pushes the ideal that the lighter your skin is, the more beautiful you are.

Skin lightening has been a practice that has existed for centuries, with darker skin being associated with menial work in the fields, and a fairer complexion being acquainted to a higher class.

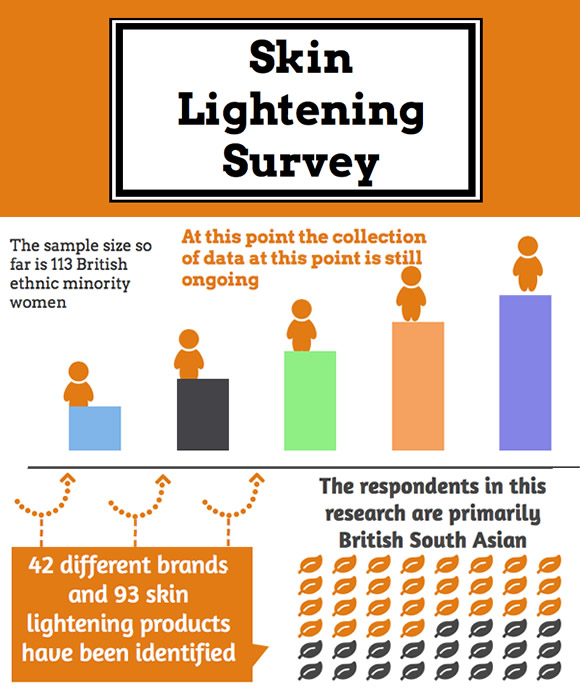

Head of Sociology and Criminology at Birmingham City University, Professor Steve Garner and Somia R Bibi have started the first real attempt to measure and understand the use skin lightening in Britain.

Their groundbreaking research will hope to reveal the health and social implications of these products in Britain for the first time.

A lot of the pressure to be as fair, pale or white as possible is entrenched in the idea that the more European you look, the more beautiful you are.

Historian at Bath Spa University, Dr Olivette Otele, told DESIblitz: “It’s not just Eurocentrism, it’s white privilege… We need to dismantle it.”

DESIblitz spoke to Professor Steve Garner and Somia R Bibi in depth about the issue of skin lightening.

What made you look into the issue of skin lightening?

Prof Garner: “I’ve been looking at identities in the UK for the last decade or so and I’m coming to the end of that cycle, looking at how whiteness impacts those racialised as white.

“I wanted to broaden the scope and think about how whiteness as a system of domination impacts on people who aren’t racialised as white, and it struck me that skin lightening is one aspect of that.

“There’s also no research on this in England at the moment. There’s lots of research about this in other parts of the world but nothing about England. Another thing is that it’s a subject that makes people engage in a passionate way.

“When I used it in a classroom six years ago, the result was that people were so enjoying it that they forgot to leave the classroom, and we forgot we were in a classroom.

“So that passed a big test for me because it suggests that people have lots of things to say about it and lots of ways to engage in it, which doesn’t happen in more dry subject areas.”

Somia: “The things you hear when you grow up, sadly. So the idea that when I was younger, no cruelty intended, when people said this but, when I heard someone say ‘oh well don’t you look nice today, you look really gori or fair’.

“Also thinking about the fact that I had relatives recommend using lemon juice in my creams to ensure that my complexion didn’t darken. Or when I talk to someone in the community and they say, ‘Isn’t that baby pretty, she’s so light’.

“It wasn’t considered anything shameful, it was a natural assumed part – the idea that fair is best.”

How do you think skin lightening has impacted the South Asian community?

Prof Garner: “Most of our sample so far has been the South Asian community. It seems skin lighteners seem to be a normalised part of a woman’s daily routine.

“The people that report using them, say that they use them everyday mainly, or some people even use them more than once a day.

“They seem to be used, firstly for a long time in your life, so people start using them early and don’t stop, and secondly they are integrated into part of their daily routines.

“They seem to be part of an everyday landscape, obviously not everybody uses them and probably most people don’t agree with them, but they are a feature of the landscape.”

What are the effects of these products on the user’s health?

Prof Garner: “There’s a very clear message in the medical literature that the use of skin lighteners, particularly the ones with toxins in them have a very direct impact on the skin and also internally, particularly to do with kidneys.

“There’s also a misleading focus on the skin lighteners that contain illegal substances like mercury and hydroquinone, which are illegal in the European Union.

“Because those things in a way are the easy things to identify, that obviously have bad effects on people’s health.

“On the other hand, the more expensive products, which are not illegal, the whole functions of those creams are to suppress melanin production.

“And melanin production is there for a reason, it helps your body protect itself from ultraviolet rays, so reducing the body’s capacity to do this increases the risk of cancer. So even the ‘good’ products in a way, are carcinogenic.”

How has social media impacted the use of skin lightening products?

Somia: “To a certain degree it depends, so there’ve been quite a few campaigns like ‘Dark is Beautiful’, but only a certain group of people seem to be aware of it.

“The campaigns been quite prominent in India and some people say that the asian community here (Britain) are aware of it, but it hasn’t saturated within.

“But even though you have these movements that can get quite big, companies are just becoming more strategic in how they sell.

“Rather than ‘whiten’, you’re ‘brightening’ or ‘illuminating’. So the idea that some companies on their websites say they are empowering women, rather than reinforcing racism.”

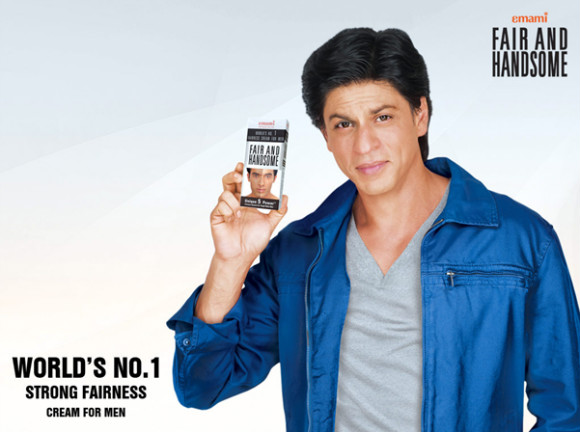

Is the use of these products gendered? Do men feel the same pressure to be light skinned?

Somia: “It feels like there is a developing case where men are starting to. Everywhere you go you see images of bodies, faces, ‘what the perfect male/female body is’ and so forth.

“The research around males and skin lightening aren’t prolific at the moment.

“But the status is changing. Look at Nur 76, which is a skin lightening brand developed in Britain by a male South Asian who also uses the products, and he’s started to disseminate the products worldwide as well.

“Male usage is on the rise, however statistically speaking, women are still the main consumers.”

Where do you think this obsession with fair skin came from?

Somia: “I don’t think it’s one factor. So I think there’s a certain level of choice when it comes to using these products.

“But we can’t ignore that individual choice doesn’t occur in a vacuum, it’s influenced by the socioeconomic environment we live in.

“Today skin lighteners are worth billions and billions of pounds. Hence why we have Fair & Lovely, Ponds, and L’Oreal advertising skin lighteners to ethnic minority groups, telling them, ‘It’ll make your life better and help you obtain the gorgeous boyfriend’.

“Also historically, as a society we like to state that we’re more progressive than what’s occurred prior to us.

“What we forget is the foundations of society, popular culture, Hollywood, were built at a time when issues around race and differentiating by skin colour and features was a naturalised part, and that’s left a legacy that has evolved, but remains key.

“The fact that there’s still economic viability and money in reinforcing these ideals, no matter how horrible it sounds, it’s profitable.

“When we say ‘fair is best’, it’s not only a binary racism between white and other, it’s also within these communities of colour.”

It’s clear from this survey that further research on the health and social implications of skin lightening is needed.

With concerns of mental health, gender, internalised racism, unhealthy vs ‘healthy’ products and so much more to consider, the issue of Skin Lightening extends much further than the pigment of one’s skin.