"The first barrier is always the family."

Alcoholism runs deep in the British Asian community but few want to talk about it.

It’s there at weddings, family dinners, and nights out, often brushed off or laughed about. Behind closed doors, though, the damage is serious and widespread.

For many, this is still a taboo subject.

This isn’t just about addiction. It’s about identity, history, and culture.

Alcohol is often visible in public but its harms are hidden, buried under shame and denial.

That silence leaves people struggling without support.

We explore the roots of the problem, the health consequences, and the lived realities of those affected. It’s time we talked about it.

The Historical Roots of a Modern Crisis

Our relationship with alcohol is complicated. It did not begin with the British.

Ancient texts speak of ‘sura’, an intoxicating drink for mortals.

But colonialism changed everything. It reshaped our connection with alcohol. The British transformed it into a tool for social control.

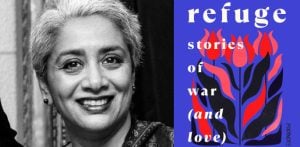

Historian Nandini Bhattacharya explains this shift.

She notes that the British made drinking a taxable enterprise. This was a response to their own failing agrarian policies. They encouraged cheap, distilled liquor among labourers on tea plantations.

This policy induced passivity. It also trapped workers in a cycle of debt.

Bhattacharya states that the British aim was to get labourers intoxicated “as quickly and as cheaply as possible”.

This colonial strategy has a long legacy. It has fostered a dangerous bond with alcohol. This is especially true for certain communities.

Thanks to this history, India is now the world’s largest whisky market.

The British effectively dismantled traditional drinking practices, replacing them with a model of heavy, industrialised consumption.

This historical context is vital as it helps us understand the problem we face today. It is a hangover from a colonial past. One that continues to poison the British Asian community.

Honour, Stigma and the ‘Open Secret’

In many British Asian families, honour is everything. The concept of ‘izzat’ governs our lives. We protect the family name at all costs.

This immense pressure creates a culture of silence and it is this silence that allows alcoholism to thrive whilst forcing the problem underground.

This manifests differently across our communities.

In some Punjabi circles, it becomes an “open secret”. Everyone knows, but no one acknowledges it directly.

Binge drinking is dismissed as “letting off steam”. It is not viewed with the same severity as other addictions. This normalisation is a form of collective denial.

In many Muslim or Hindu families, the taboo is more absolute. The religious and cultural prohibitions are stronger. Here, an alcohol problem is not an open secret, but a source of profound shame.

Therapist Farah Chowdhury says: “The first barrier is always the family.

“The individual might be ready to talk, but they are terrified of bringing shame on their parents. The guilt is immense.”

This fear stops people from seeking help. The silence, meant to protect honour, becomes a cage.

Masculinity and Social Pressure

Within some British Asian communities, drinking is welded to masculinity.

Alcohol consumption is not just accepted for men; it is glamorised. It is seen as a social norm. A rite of passage.

This attitude fuels a dangerous culture of excess.

Cultural events often encourage this behaviour.

Think of a wedding reception. The whisky flows more freely than water. Men are expected to drink heavily. To refuse a drink can be seen as an insult.

This pressure is immense and it normalises binge drinking. It turns a health crisis into a cultural celebration.

The infamous “Patiala peg” is a prime example. It is a measure of whisky far larger than the standard. It is a symbol of pride in excessive consumption.

This social dynamic creates a perfect storm. Young men grow up believing that heavy drinking is normal.

The stresses of migration and racism can also be a factor. Many men turn to alcohol to cope with these pressures.

Alcohol becomes a crutch. But it is a crutch that cripples.

This toxic bond between alcohol and manliness needs to be broken, as it is a bond that is costing lives.

Women and Secret Drinking

If alcoholism is a man’s open secret, it is a woman’s buried shame.

The stigma faced by British Asian women with alcohol dependency is doubled. They face the general taboo of addiction. And they face the specific cultural sin of being a “bad woman”.

Traditionally, a woman drinking is rarely public. It is something that happens behind closed doors.

In public, she is expected to be the perfect daughter, wife, and mother as she is the guardian of the family’s ‘izzat’.

An alcohol problem shatters this image completely.

The fear of being discovered is paralysing. This leads to solitary drinking, a particularly dangerous form of dependency.

It fosters deep isolation and makes asking for help almost impossible.

Their struggle remains largely invisible. They may be high-functioning, managing households and jobs. But they are trapped in a cycle of secret consumption and overwhelming guilt.

Unlike men, their drinking is never celebrated or excused as “letting off steam”.

It is seen as a moral failing of the highest order. This deep-seated prejudice means countless women suffer in total silence, cut off from any chance of support.

Health Risks

The health consequences of alcoholism are severe for everyone.

But for South Asian heritage people, the risks are alarmingly specific. Our genetic makeup can make us more vulnerable.

Some South Asians have a deficiency in an enzyme called ALDH2. This enzyme is crucial for metabolising alcohol.

Without it, a toxic compound called acetaldehyde builds up.

This substance directly damages DNA and this damage can cause cells to grow uncontrollably, leading to cancer. It significantly increases the risk for at least seven types of cancer, including liver, colon, and oesophagus.

GP Dr Ahmed* says: “I see the signs in routine blood tests all the time.

“High liver enzymes in a patient who swears they only drink at weddings. The family rarely acknowledges the real issue.”

South Asians already face a higher risk of metabolic syndrome, which can lead to diabetes and heart disease.

Regular heavy drinking pours fuel on this fire. It can lead to insulin resistance, a precursor to type 2 diabetes.

Breaking the Cycle

The journey out of alcoholism is difficult. But it is possible. Ibah Shah‘s story is one of hope.

Growing up as a queer Pakistani, he felt overwhelmed. Alcohol became his escape.

He was a straight-A student. But his life spiralled out of control. He lost his job, his car, and found himself drinking all day.

Ibah hit rock bottom after a DUI. His addiction remained a secret from his parents for years. It was only after the death of his mother that he found the strength to stop.

Today, he counsels others.

Ibah advises:

“A bigger and better life is possible.”

He encourages people to ask for help. He knows it is not easy. But he promises it is worth it.

His experience highlights a crucial need. We need more culturally sensitive support services.

Mainstream services can feel alienating. People need to feel safe and understood. They need to know their confidentiality will be respected.

Ibah Shah’s story proves that recovery can happen. The path may be different for a man facing public pressure or a woman facing private shame. But the cycle of addiction can be broken.

The silence surrounding alcoholism in the British Asian community is a profound betrayal.

It is a crisis that has unfolded in households for too long.

This is not just a personal failing. It is a community problem, one with roots in South Asian history and branches that touch every family.

The cultural pressure, misplaced honour, and wilful ignorance have created a devastating legacy.

The time for looking away has passed.

The toxic masculinity that fuels binge drinking must be challenged. Safe spaces must be created for mothers, sisters, and daughters to speak openly. The health risks are too severe, and the personal cost is too high.

This conversation needs to begin now, in living rooms, in community centres, and across the South Asian diaspora.

Breaking this generational curse is a collective responsibility. The health and future of the community depend on it.