"At least 300,000 Ugandans lost their lives"

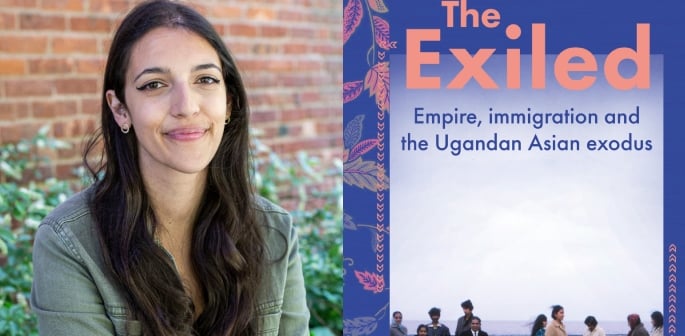

Lucy Fulford, an accomplished multimedia journalist and filmmaker, stands at the forefront of the league of storytellers.

Her latest venture, The Exiled, is a narrative non-fiction masterpiece that unearths a chapter of history obscured by time and overshadowed by political narratives.

The book transports readers to Uganda in August 1972, a pivotal moment when President Idi Amin stunned the world – the expulsion of all South Asians within 90 days.

As they dispersed across the globe, countries like Canada, India, and the United Kingdom became the new homes for these expellees.

The UK, in particular, welcomed more than 28,000 individuals, offering them a chance to rebuild their lives.

However, the stories of resilience, pain, and courage that emerged from this diaspora have, until now, remained largely hidden.

What sets The Exiled apart is Fulford’s commitment to unveiling the truth.

Drawing on first-hand interviews and testimonies, including those from her own family, the book becomes a vessel of silenced voices.

Through this lens, politically expedient narratives are dismantled, and the true fate of minorities at the end of the empire is brought to light.

With affiliations linked to organisations such as The Society of Authors, Women in Journalism, and the Women’s History Network, Lucy Fulford’s commitment is undeniable.

We caught up with the author to speak about The Exiled, the inspirations behind it and her thoughts on Ugandan history.

What influenced your interest in migration and conflict?

Migration, both voluntary and forced, is part of my family’s journey, so it’s also a part of who I am.

It has, on some level, perhaps given me a natural affinity towards the subject.

Growing up in a newsy household, where there were always daily newspapers around and discussions of current affairs, I’ve been interested in the world from a young age.

A lot of what affects the news is migration and conflict, and they are, of course, linked.

When I became interested in journalism, like many, I was inspired by war correspondents.

There’s something essential about humanity in conflict situations.

But I am less interested in the frontline and the mechanics of armed conflict, and instead about the way war affects everyday people.

I think migration and borders are some of the core issues of our times.

We see this in their pollicisation and the vilification of those travelling in search of safety or brighter prospects.

We’ll increasingly see it even more as climate change forces people to move away from the places they call home.

What inspired you to delve into the history of Ugandan Asians?

This history is my family history, so in many ways, I have been thinking about it my whole life.

My grandparents, mother, aunt and uncle were among the 50,000 exiled from Uganda in 1972.

“So, I had always been curious about this largely unspoken part of the past.”

I grew up hearing stories of life in Uganda, generally, the kinds many Ugandan Asians share, around happy childhoods, temperate weather, and lush and plentiful tropical fruit.

As I grew older, I started to understand the wider forces at work beyond the fact a dictator had forced them to leave their home.

Studying history at university, I became more interested in the post-colonial years in East Africa, including looking at the Mau Mau revolt in Kenya and the Rwandan genocide.

As we approached the 50th anniversary of the landmark Ugandan Asian expulsion in 2022, I started thinking of how I could approach the subject journalistically.

What originally started as a photography project, quickly grew into a bigger narrative one.

I realised that with so many people knowing little to nothing about this period, I wanted to weave together the many strands from the personal to the political to tell this story more comprehensively.

Did you encounter any poignant stories during your research?

I was able to hear incredible stories when gathering testimony, from Kausar, now living near Birmingham, who escaped Uganda and raised a lion cub in Kenya.

One of the things I found most poignant was hearing about the reconnections Ugandan Asians made years later with Ugandans they or their families had known in the years before the expulsion.

Two women I spoke to both shared how their paths unexpectedly crossed with people who used to work for their parents.

Both shared how their lives were also devastated by the Amin years.

I think it’s important to recognise that when we talk about the Ugandan Asian story, it was the Ugandan population who suffered the most under Amin’s rule, which is often overlooked.

It’s thought at least 300,000 Ugandans lost their lives at the hands of the military state, but others put the devastating losses closer to 800,000 or 1 million.

How did you approach the challenge of uncovering this period of history?

I wanted to write history with a narrative, journalistic voice, to create something that was page-turning, and far from the dry history books which put so many off history in school.

For me, the way to engage people is through individual stories.

So almost every chapter leads with something personal, which then broadens out to the wider historical context.

We find out about the fate of minorities at the end of the empire in their own words.

From my grandparents’ wedding day in Kerala to climbing up the minaret of Uganda’s largest mosque, I hope The Exiled transports readers to different times and places around the world.

“Along with this, I needed to back up my storytelling with rigorous historical detail.”

I combed through government documents, archived newspapers and TV reports, along with contemporaneous analysis and more recent historical and sociological research.

I knew within the scope of this book I couldn’t be exhaustive in my exploration of this expansive period.

But I have tried to showcase the side that has been explored less to date.

I’ve moved away from stereotypes of victimhood and wealth, towards a more nuanced understanding that brings us right up to today.

What important lessons can readers gain from the book?

One of the major lessons for me is that we don’t always learn from the past.

Anti-immigration rhetoric which was being spouted in the 70s can at times be indistinguishable from what we hear today.

Edward Heath’s government genuinely researched island territories to offshore future migrants from colonies or former colonies, such as the fear of widespread migration of people of colour to Britain.

And today we have leadership tripping over themselves to move asylum seekers to a country that borders Uganda.

Part of the reason why I wrote The Exiled was to explore the complexities and contradictions.

Too often, on the rare occasions when this history is discussed, it verges into stereotypes and becomes a tale of success stories of affluent business-minded people.

Ugandan Asians are more than ‘good migrants’ and we should be more than to buy into this rhetoric, which is used in turn to tarnish other migrants.

The book also shows, more positively, how migrants have reshaped this country, for the better.

How does reporting in diverse environments shaped your approach to storytelling?

At the heart of all reporting lies the same things – being open, honest and empathetic, actively listening, and being meticulous in your assessment of what you’re witnessing.

Starting out in daily news was a great training ground in getting to grips with new things fast, and in learning to relate to a wide range of different people.

When you’re meeting people in some of the worst moments of their lives, or encouraging them to remember them, it’s vital not to add to the difficulties, or re-traumatise people.

Sometimes that means stepping back when you might otherwise want to push forward for the sake of the story.

In a conflict environment, you have the added pressures of bias and propaganda to wade through.

In many ways, this was helpful when it came to my work on The Exiled because I could look critically at material, and challenge myself regularly on any internal biases I may have.

“Most of all, reporting in diverse environments has shown me the value of sharing stories.”

I’m a strong believer that everyone has something interesting to say, if you ask the right questions at the right moment.

Everyone wants to be seen and heard, and to be able to facilitate that, anywhere, is a privilege.

Were there any experiences that shocked you the most?

The Exiled seeks to put human faces onto the numbers.

When we hear 28,000 people came to the UK over a few months, it can be hard to relate to it.

But when we hear about Kavi being chased by skinheads on his way home from school in Leicester, or Lata making her way through a children’s home having been split up from her parents, we connect with it.

One of the things that has really stayed with me is the way the traumas of the expulsion have moved down the generations.

Although for most the expulsion wasn’t overtly bloody, the spectre of violence hung over all of it.

That fear doesn’t go away overnight.

And one woman in the book shares how assimilation can split a family.

She and her brothers came to the UK in 1972 while her parents, due to visa restrictions, went to India.

Separated by British policy for several years, when they saw each other again, they didn’t even speak the same language anymore.

Displacement comes with all kinds of hidden pain.

How does displacement resonate with you personally?

As well as my family’s migrations, when I was 12 I moved countries too.

There is a sense of dislocation that comes from leaving a life behind that’s hard to explain unless you’ve gone through it.

For me, this manifests in the what-ifs.

What would have happened if we hadn’t moved? What kind of person would I have become?

Growing up between cultures, with Indian and British sides to my family, and living in Australia in my childhood, I became interested in exploring the tensions between the different parts of us.

One of the huge advantages I had writing this book – being personally connected to this material – was also one of the greatest challenges.

“In my journalistic work, I am used to covering stories which I am not a part of.”

The Exiled meant I was intimately connected to the histories people were sharing with me.

This allowed me to connect with my interviewees on a new level but also made the whole process feel more vulnerable.

How has the Penguin WriteNow program helped you?

The publishing industry has long been opaque, so it’s great to see the range of access schemes run today, such as Penguin’s WriteNow and HarperCollins’ Author Academy, both of which I was fortunate to be selected for in 2020.

Being longlisted for WriteNow was the first confirmation that both my idea and writing had legs, and it gave me the confidence to keep going.

But by far the best takeaway has been the other writers I have met through it.

Having community is key, especially when you are working on topics which can be typecast as minority issues, not of interest to mainstream audiences.

I’ve needed to lean on a supportive network on my journey to publication and beyond.

When covering complex histories, it’s important to remember your work can’t be everything to everyone, so stay true to your mission, and back that up with vigorous, balanced research.

I would suggest aspiring authors get involved with as many writing community events as they can.

Any feedback you can get will make your work stronger, your skin thicker, and there’s every chance you’ll meet some of your closest friends in the process.

How do you envision the book contributing to discussions about migration?

Empire is a touchy subject in the UK, and taking a critical view of the past can prove unpopular with people who would rather we didn’t speak about it.

But far from being distant history, as the imperial years are often presented, we are within touching distance of it.

The expulsion, in post-colonial years, was just over 50 years ago, well within living memory.

Uganda had only gained its independence one decade prior to that.

“The impact of these events is alive within descendants.”

In terms of migration, I think the Ugandan Asian story neatly encapsulates so much that is wrong with our modern migratory policy and politics.

People weren’t wanted due to the colour of their skin, generous volunteers helped step in where the state didn’t, and politicians obfuscated the truth and then took the credit.

I would love it if people reading The Exiled felt more connected to the past, realised how the aftershocks of empire still reverberate to this day and became curious about their own family histories.

Can you share any future projects that you’re excited about?

When I first studied history, I was fascinated with famous leaders, like the dictators that shaped Europe and Russia during the World War II years.

Social history seemed somehow less exciting.

Now, I couldn’t feel more differently.

Although Idi Amin is at the heart of the expulsion, I didn’t want to write a book centring him. It’s too simplistic.

We need to understand the wider forces – like the British Empire – and the everyday experiences to get hold of the past.

My interests lie firmly around individuals and communities going through change, particularly experiencing the echoes of violence from war or the displacement of forced migration.

There’s a lot more to the wider East African Asian story across Kenya and Tanzania than I was able to go into in The Exiled.

I am also exploring work around women caught up in conflict, along with generational trauma.

In the pages of The Exiled, Lucy Fulford invites readers to traverse continents and decades, unveiling the stories of courage, pain, and resilience.

We recognise that The Exiled is more than a book; it is a testament to the indomitable human spirit and a bridge connecting the past with our present.

Lucy Fulford’s exploration of identity and generational legacy becomes a mirror reflecting the shared human experience.

Grab a copy of your own here.